UC BERKELEY WOMEN AND GENDER STUDIES

COMMENCEMENT SPEECH

“BLAZING FORWARD”

THIS IS THE TEXT OF A SPEECH I GAVE FOR UCB’S WOMEN AND GENDER STUDIES GRADUATION IN MAY 2013. ENJOY!

Thank you so much for this generous invitation to speak to you today as you, the class of 2013, prepare to go out into the world as graduates of the UC Berkeley’s Department of Women and Gender Studies. I know that you have chosen me to speak on account of my path-breaking work on decoding Dude, Where’s My Car? Finding Nemo, Fantastic Mr. Fox and other canonical texts and I know that you are unsure about my commitments to Lady Gaga, my critiques of gay marriage and my seemingly odd and perverse attachment to “the queer art of failure”; but I also know that you trust me to lead you astray, counsel you in the counter-intuitive and tell you what I think about life, love and sex toys.

Seriously Dude, where is my car?

This day represents four years of hard work, hard play and the hard times of explaining to your parents over and over again what it is you do as a Women and Gender Studies Major; but now is the time to put all that you have learned into motion and to take responsibility for the privilege of having been afforded the opportunity to read, write, think and converse with others on arcane and whimsical topics alike.

“Blazing forward” is our theme today and so I want to think with you about the future, about the past, about momentum and about what it really means to blaze a new trail, to take a new route, to think differently and to move forward with rather than ahead of others. I thought deeply about your theme the other day as I sat watching “How To Train Your Dragon,” a Dreamworks animated feature film from 2010. There are many lessons in “How To Train Your Dragon” that we can use here today to think about the future – there are also fire breathing animals so that connects nicely with your theme of “blazing forward,” and I will be returning to this text throughout my speech so don’t think that you will be enduring a long plot summary for nothing.

In this film, a group of Scottish Vikings live out short days and long nights on the Island of Berk. The village is periodically attacked by a multi-species alliance of fire-breathing dragons, and the villagers spend their lives training to ward off, capture and kill the creatures that fill their nights with terror. The useless cycle of attack and defense claims lives and limbs until an enterprising young person, named Hiccup realizes, after wounding a Night Fury, a rarely seen but deadly bat-like dragon, that there has to be a better way. Hiccup, who is a disappointment to his father and a failure in the masculinity department, finds the wounded dragon and rather than killing it, he names it Toothless and befriends it. Hiccup helps Toothless, to fly again by designing and building a prosthetic tail for him—making for a queer and kinky alliance between boy and dragon—and he uses his friendship with Toothless to create peace between the dragons and Vikings. As Hiccup tells Astrid, a fearless and tough female dragon fighter, “Everything we ever believed about the dragons is wrong.”

The film thematizes the usefulness or uselessness of “training”; it also thinks carefully about how and why to live peacefully with other forms of life, even with some that seem to threaten you; and it argues for complexity, creativity, improvisation, gender queerness, cooperation and risk over normativity, the violence of its enforcement, scripted behaviors, competition and safety. The film allows Hiccup and Toothless to form a bond through their weaknesses and their outsider status, their injuries and their vulnerabilities and it shows how they grow together not by competing but by training each other, learning from each other and, ultimately, saving each other. Toothless learns to fly with a broken tail and Hiccup learns to ride him with a broken foot. The film also has some pretty great scenes involving prosthetic body bits, leather harnesses, flight, invention and the physics of navigation.

The film thematizes the usefulness or uselessness of “training”; it also thinks carefully about how and why to live peacefully with other forms of life, even with some that seem to threaten you; and it argues for complexity, creativity, improvisation, gender queerness, cooperation and risk over normativity, the violence of its enforcement, scripted behaviors, competition and safety. The film allows Hiccup and Toothless to form a bond through their weaknesses and their outsider status, their injuries and their vulnerabilities and it shows how they grow together not by competing but by training each other, learning from each other and, ultimately, saving each other. Toothless learns to fly with a broken tail and Hiccup learns to ride him with a broken foot. The film also has some pretty great scenes involving prosthetic body bits, leather harnesses, flight, invention and the physics of navigation.

Like Hiccup on the back of Toothless then, you are about to blaze forward into a world that, like Hiccup’s world, is aflame with violent conflict, misunderstandings, amped up competitiveness, toxic Viking masculinity, and seemingly insurmountable divisions between people who care only about money, profit and security and the rest of us who really do want to wrestle with the hard problems of administering social justice, preventing environmental collapse, redistributing wealth and making health care and education available to all.

is aflame with violent conflict, misunderstandings, amped up competitiveness, toxic Viking masculinity, and seemingly insurmountable divisions between people who care only about money, profit and security and the rest of us who really do want to wrestle with the hard problems of administering social justice, preventing environmental collapse, redistributing wealth and making health care and education available to all.

In my book The Queer Art of Failure, I argued that in an age when our formula for success has become fused with making money, failure might offer us a critique of capitalism. And in an era when the only successful relationship is seen as one that lasts forever and is recognizable to the state, failure might offer us an avenue to alternative intimacies. Of course, success and failure are always tethered to one another – one person’s success in this zero-sum economy necessarily seems to mean another person’s failure and so as the richer get richer, the poor get poorer; as middle-class white people feel safer, more people of color go to jail; as one group of gays and lesbians feel recognized by the state, another group falls into the category of the illegitimate; as borders become secure, the lives of undocumented workers become ever more precarious. Nothing ever happens to only one of us, everything always happens to all of us.

Success and failure happen to all of us and it is time to start thinking about how to live and thrive without causing others to crash and burn. But having said that, can we think of ways to make success a more capacious category and to make failure less of a dumping ground for the toxic waste created by success and more of an alternative terrain – a training ground if you like – where people come to rethink their investments in static American Idol types of models of winning and losing and begin to expand their understandings of what it would mean to move forward. One thing we learn in Women and Gender Studies over and over again is that there is nothing natural or inevitable about hierarchies – gender hierarchies have sustained the power of fathers over mothers, men over women, cis-gendered people over gender variant people; class hierarchies allow for the exploitation of workers by management; racial hierarchies implicitly and explicitly map out certain futures for some people and they foreclose futurity itself for others. Sexual hierarchies, as Gayle Rubin’s work demonstrated some thirty years ago, sustain all kinds of moral orders that more properly belong to religious systems and they maintain a social mistrust of sexual pleasure while inhibiting what she calls the possibility for erotic justice.

In Women and Gender Studies departments such as this one, we learn to challenge the idea of the “natural”; we learn to think in terms of performance and performativity; we learn to question our own privilege, to create histories of the present, geographies of oppression, theories of subjectivity, philosophies of being and becoming, epistemologies of the closet …and, we learn, if we are smart, how and when to say no, why and to whom to say yes and what the consequences might be of saying “Call Me Maybe.”

In Women and Gender Studies departments such as this one, we learn to challenge the idea of the “natural”; we learn to think in terms of performance and performativity; we learn to question our own privilege, to create histories of the present, geographies of oppression, theories of subjectivity, philosophies of being and becoming, epistemologies of the closet …and, we learn, if we are smart, how and when to say no, why and to whom to say yes and what the consequences might be of saying “Call Me Maybe.”

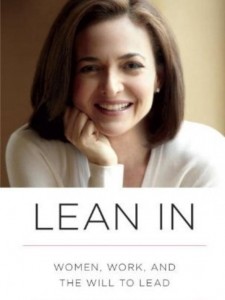

Indeed, a Women and Gender Studies major, once set loose upon the world, knows better than to “lean in” with Sheryl Sandberg and others who don’t care about corporate greed, but who just want to offer women a seat at the table. CEO’s like Sandberg, in recent years, have hit the jackpot selling a twisted version of feminism back to women: Sandberg makes lots of sense with her aphoristic advice to women who are climbing up the corporate ladder – she urges women to leave the side-lines and live center-stage in a corporate office; she wants women to insist on their male partners doing 50% of the domestic labor and, she counsels women to capitalize on every opportunity that comes their way professionally and to worry less about being likable. Good advice all of it but, like the girl in How To Train Your Dragon, Astrid, who just wants to be as successful as the boys at killing dragons, this advice leaves the structures of inequity in place, never questions the project of making a killing at the expense of others, and finesses the models of success inherited from masculinist corporate culture rather than constructing new models, as Hiccup does, with different goals for cohabitation.

In How To Train Your Dragon, the question Hiccup confronted head on was how to succeed as an alternatively gendered person in a male world. The questions Sheryl Sandberg crafts, however, are all about how to make your mark, your money, your individual path to success. Without ever questioning the ethics of corporate warfare on the one hand or the costs that we all pay when corporate managers—male or female or other–take more and more of the profits and when regular people take on all of the losses, Lean In tells you that “you” can

Go ahead, hate her…

have it all. That notion of “having it all,” like the recent anti-bullying slogan “it gets better” masquerades as an activist agenda while actually sneaking a neo-liberal agenda of freedom for the rich from regulation in the back door. When we promise white women that they can have it all, aren’t we actually saying that someone else can have nothing? When we promise white kids that “it gets better,” we might unwittingly be confirming that for many children facing futures of poverty, racial discrimination or deportation, it will definitely get much, much, worse. The empty pronoun “it” in each cliché holds the empty promise in place: what if instead we said to all genders, you can have “some of it” or what if we promised kids: “it gets weirder, it gets wilder, it gets worse then better, then worse, then just blah.” We might be more honest if we said: “it gets hotter” in an era of global warming, or “it gets dirtier.” What if we did not have to resort to clichés because we were actually educating our children at all levels and to the highest level instead of applauding corporate climbing while defunding public education.

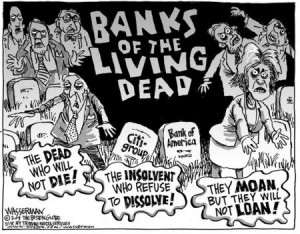

In this day and age, the point is not to kill the dragons, to refine forms of violence, to finesse the rise to the top. We live in an era where your generation has said enough is enough – you don’t just want an occupation, you want to occupy. You don’t just want a corner office, you want to rethink the value of work. You don’t just want to pick up your degrees today and go on your way, you want to think long and hard about the contradictions that you are inheriting along with massive debt and global social unrest. My generation has asked yours to go into debt to pay for something that should be free; we have expanded the individual human life span in developed countries and shortened the life span of the globe in the process. People on the right say they care about life when it comes to issues like abortion but then vote to bomb civilians using unmanned drones in the Middle  East. We don’t want to give welfare to the poor but we bail out the banks. We drill the wilderness for oil but do not develop better public transit systems. We coo and fuss over baby kittens and dolphins but then we trap, maim and slaughter animals in an industrialized food chain that produces waste, toxicity and obesity. This is a complicated world full of dangerous dragons and we cannot just keep killing things one at a time and training new generations to do the same.

East. We don’t want to give welfare to the poor but we bail out the banks. We drill the wilderness for oil but do not develop better public transit systems. We coo and fuss over baby kittens and dolphins but then we trap, maim and slaughter animals in an industrialized food chain that produces waste, toxicity and obesity. This is a complicated world full of dangerous dragons and we cannot just keep killing things one at a time and training new generations to do the same.

I remember when I went to UC Berkeley in the early 1980’s. The Bay Area was a very different place then – Berkeley was more like Hiccup’s village of Berk than the upscale college town that it is today; and Berkeley was still alive with the after-glow of the radical movements of the 1960’s and 1970’s and was the site of a full-fledged divestment movement against Apartheid in South Africa. You could still buy a house that you actually wanted to live in for less than a million dollars, and bohemian thinkers, writers and artists moved in and out of the area leaving their mark. There were women’s bookstores in Oakland and San Francisco, lesbian bars in the Mission, diverse populations lived side by side with different degrees of equanimity. And I am not simply saying that those were the good old days…but they were different days, days before the property market boomed, before Silicone valley expanded, and before gay marriage engulfed all of our queer activist energies. In those days there were lots of fights too – between sex positive and sex negative feminists, between lesbians and gay men, queer gentrifiers and poor communities of color renting their homes in neighborhoods like the Western Addition. I was a diffident student at that time – I showed up for classes every now and then, I lived in the city, worked in a bookstore with a member of the Chinatown communist party, and I Dj’ed occasionally. I took my education for granted in a way you never can, and I chatted with other women studies majors about “smashing patriarchy” (See sometimes it does get better…). I was more like Astrid than Hiccup, ready to fight every dragon, training to be the best fighter I could be and never questioning the whole project of fighting in the first place. I would like to think that nowadays we are training each other to be less conflict oriented and more inventive in our responses to the challenges we face; I would hope that we are in the game less to win than to make up new rules and new outcomes. But I realize that pressures on you today are very different from the pressures your parents faced when they were in college.

My point is, there was less pressure on us in the 1980’s to make a living and to think of success only in terms of marriage and money. And so, as you leave here today, degree in hand, ready to go off and slay, befriend or train some dragons of your own, it might be a good time to reflect on what you want to be and to come up with some creative answers to the questions of your time. In this day and age, I hope you are not planning to become the investment bankers/white collar criminals, let alone the lawyers who defend then, and I really hope you are not working here in the hopes of using feminism to increase the number of women ripping everyone off! I hope that the education you have received here has taught you to see through the contradictions of capitalism, the shallow freedoms of a neo-liberal free market and the narrow ambition of feathering your own nest.

A Women and Gender Studies major knows that transformation not accommodation is the real goal, and that terms like “equality,” “liberty,” “freedom” and “representation” often smuggle other inequities and other forms of bondage into the social contract. Having learned well how to maintain a healthy amount of skepticism, how to think beyond platitudes and how to smoothly escape from a mansplainer, the Women and Gender Studies Graduate can separate good from bad advice, knowledge from clichés, and she knows by now to mistrust anyone who tells you that you just have to be yourself, to follow your dreams or to seize the day. She also knows never to take sex tips from Liz Lemon when she counsels: “A lady always leaves her blazer on.”

But from blazers back to blazing forward – from clichés to what it means to truly learn, from making war to living with dragons, let me conclude by returning to Hiccup and Toothless as they defy war, man and gravity. After Hiccup has downed the Night Fury dragon he plunges into the woods to find the creature. Finally, he comes upon the wounded animal, lying on its side, waiting to die. At first, Hiccup is proud of what he has done: “I did this!” He yells, “I did it! This, this fixes everything. Yes, I have brought down this mighty beast.” He approaches the dragon and, well taught by Sheryl Sandberg, he leans in, sword raised, eyes fixed upon his prey, ready at last to take his place, as a gender queer subject, at the Viking table of life. He raises his sword, he prepares to plunge and then he catches the dragon’s eye as it waits to die. Hiccup pauses, drops his arm, leans back and says: “I did this…” This quiet moment of accountability is all that anyone is asking for as a prelude to another way of being in relation to others – I did this! A better mantra to live by than having it all or hoping that it gets better. I did this! Once we reckon with what it means to do, to be and to act in relation to others, we are ready – ready to train and be trained, to ride and be ridden, to love and be loved, to give and be given, to accept and reimagine. You, Women and Gender Studies Majors of UC Berkeley, class of 2013, you are ready to ride your dragons, to ride with them, to blaze forward, to make change. We wish you well, we are proud of who you are and want to be proud of who you will become but for now, take a moment to congratulate yourselves for the hard work you just completed: you did this, all of you and on behalf of all of us, I thank you.